What is the Heilmeier Catechism? And why is it important? Vertx explores how to draft a winning proposal in 8 easy steps.

What is the Heilmeier Catechism?

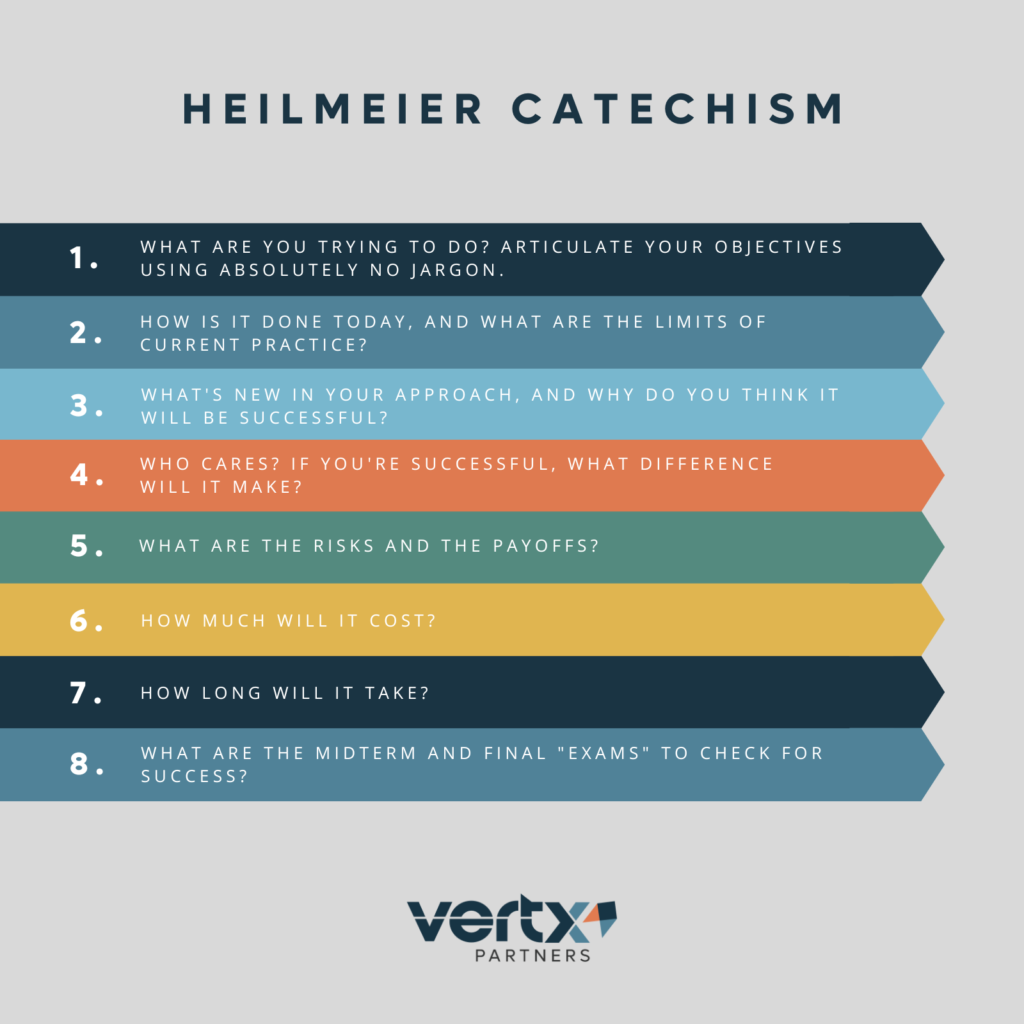

The Heilmeier Catechism is a set of 8 questions formulated by George H. Heilmeier. He posited that innovators proposing an R&D project, like a Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) or Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) contract, had to answer these 8 questions to craft a strong, convincing proposal.

Heilmeier was an engineer from Philadelphia. Over the course of his illustrious career, he worked in both the public and private spheres. He first worked with the Department of Defense in the 1970s before becoming director of the Defense Advanced Researched Projects Agency (DARPA) in 1975. He left the government in ’77 to serve in executive positions for Texas Instruments and Bellcore.

While Heilmeier’s legacy includes pioneering liquid-crystal display (LCD) screens, his Heilmeier Catechism is still familiar to many contractors.

Importantly, federal officials tasked with reviewing and evaluating proposals are also familiar with the Heilmeier Catechism and continually ask themselves if a given proposal can adequately answer its posed questions.

Heilmeier’s Catechism cataloged the following 8 questions:

1. What are you trying to do? Articulate your objectives using absolutely no jargon.

Here’s a question that is so self-evident in its necessity for an answer that you may question its inclusion within the catechism. However, we find the clincher in the last term: jargon.

The nitty-gritty of a proposal often bogs down proposal writers. They become so focused on the technicality of their project that they forget their audience.

Being able to sell an idea in simple terms is persuasive for two reasons:

- From a functional perspective, there are fewer chances of misunderstanding.

- The hallmark of a good idea is simplicity.

2. How is it done today, and what are the limits of current practice?

This is your chance to explain both your understanding of the topic at hand and the shortcomings of contemporary practice. Essentially, this is the stage of the proposal where you identify the problem you’ll be proposing a solution to.

This is a crucial step in the proposal process because it lays out several of the stakes you think you have an answer to; maybe a process or product is more dangerous or costly than your alternative, and then your proposal looks that much better by comparison. Check out our guide to the SWaP-C principle for more.

3. What’s new in your approach, and why do you think it will be successful?

Here’s where you start going into detail about your proposal. With the stage set for current practices, you can now explain how your approach subverts that practice and – most crucially – why your specific method is successful. Success here is defined as remaining functional while improving on an obsolete procedure or product.

4. Who cares? If you’re successful, what difference will it make?

This is a follow-up to the previous question. You have two tasks before you with this question: you need to list the pros of your updated product, and you also need to keep in mind who will benefit here. This is a chance to name potential benefactors who will reap the rewards of your innovation.

5. What are the risks and the payoffs?

Here’s where you need to be honest with the evaluators. You’ve thought of something they haven’t, so now you need to be upfront about risks – if you can’t or do not name all the risks in your proposal, then the evaluators will name their own.

Naming drawbacks in your own proposal gives you a strategic leg-up because it allows you to extend rebuttals; the more you omit, the more skeptical evaluators will be.

6. How much will it cost?

We’re talking dollars and cents here. This is straightforward but calculating cost and showing your math helps build your case. You can’t expect the evaluators to be charitable with your proposal, so make sure you don’t skip this step – remember, you’re selling a product here, and the first thing any buyer wants to know is, “How much is this going to set me back?”

7. How long will it take?

Following the logistical theme here, everything has a cost and a timetable. How long does it take to train workers to perform your task? How long will it take to implement? Develop? No one likes their time wasted, but this is an aspect often overlooked by proposal writers.

Again, don’t expect evaluators to be charitable in their estimations – give them your estimate and show your math. The more detailed you are in your explanation, the less pushback you’ll experience.

8. What are the midterm and final “exams” to check for success?

Your final question requires that you break down your timetable and establish benchmarks for success. Proposals are rarely as simple as going from Point A to Point B, so setting realistic checkpoints as a barometer for achievement helps sell your proposal as thought-out and achievable.

Beyond the Catechism

The Heilmeier Catechism is not intended to function as a holistic standard for evaluation – plenty of proposals answer all of these questions in satisfactory detail but get rejected for other reasons. However, savvy proposal writers keep it in mind in order to boost their chances of success.

Vertx Partners commits itself to providing resources and education for first-time and veteran businesses looking to land a contract with the federal government. Interested in joining our growing network of Appalachian businesses, entrepreneurs, researchers, and innovators? Contact Vertx today.

Become an Innovator With Us

Tell us about yourself, answer a few questions, and hit submit. It’s as easy as that to get started.